Stories

From Gail Merrifield Papp’s new memoir

Persuading Joe to read The Normal Heart

My first lunch with Joe

(excerpted from the chapter “Malacology”)

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s memoir.

with Joe

Project

deserted road

(excerpted from the chapter “Malacology”)

I was something of a loner in these early days at The Public Theater. Although I had friendly relations with the small staff from the Great Northern Hotel when we had all moved into the Astor Library building, I seldom went out to lunch like the others did, and I was never on the inside track of office gossip.

Now he was asking me? I didn’t know what to make of it. Actually, I felt like hiding, but, as with Joe’s scary request that I take his director’s notes at Troilus and Cressida previews during my first summer, I couldn’t think of a plausible reason to say no. So, as I had done then, I said “Fine.”

“If I had permitted myself to be more vulnerable, I would have continued in the acting profession,” Joe said, “but the ego of an actor is a very difficult thing to have to cope with because you yourself are the instrument.”

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

Stories

From Gail Merrifield Papp’s forthcoming memoir

Persuading Joe to Read The Normal Heart

(excerpted from the chapter “The Normal Heart”)

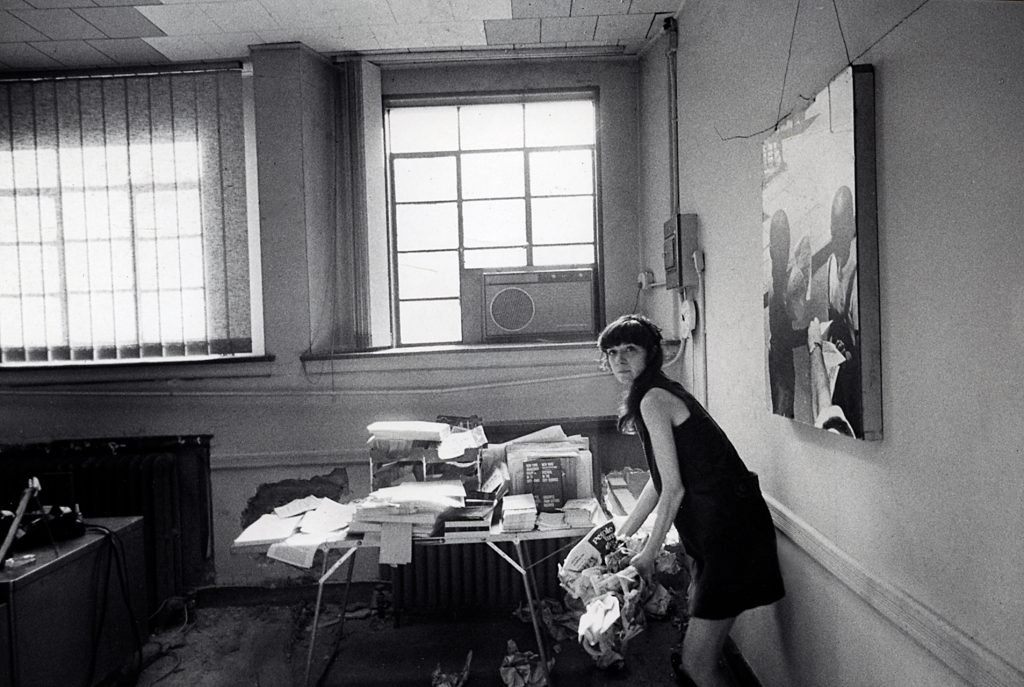

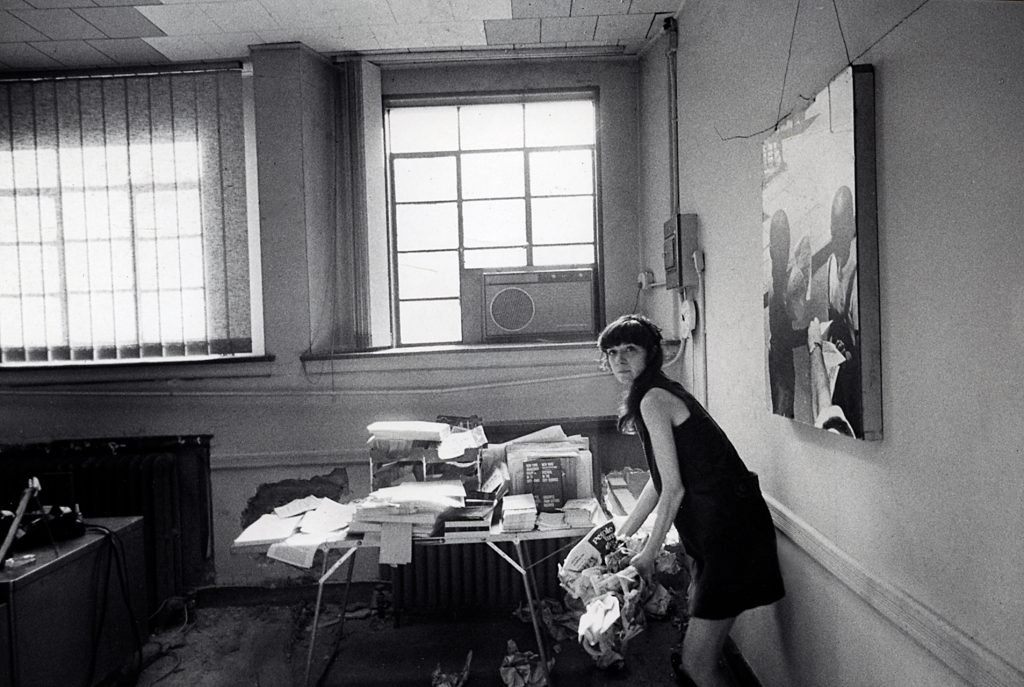

Photo: Gail Papp

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

(excerpted from the chapter “The Normal Heart”)

Photo: Gail Papp

But I knew that persuading him to read Larry Kramer’s The Normal Heart wouldn’t be an easy task because, despite my privileged access to Joe, I had learned that there was never a good time to ask him to read a play. Regardless of the circumstances, it spoiled his mood and interrupted something that had a greater claim on his attention. In addition, Joe was habitually doubtful that recommendations ever proved to be worth their salt, and I was in no way exempt from that standard, so there were many reasons for me to severely test my judgment before recommending a script to him.

Since The Normal Heart was too long to read in one sitting at the office, I brought it home. Taking a deep breath, I said to Joe, “Here’s a play that deals with a really important issue. It needs a lot of work, but it’s full of passion and I think you should read it.”

Putting myself on the artistic line with Joe was a nerve-wracking business. I wasn’t shielded from his stern verdict about the worthiness of a play any more than anyone else was. I felt confident about The Normal Heart, however, not because it was timely or political, but because it had made me cry, something that rarely happened when I read a play.

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

Stories

From Gail Merrifield Papp’s forthcoming memoir

The Belasco Project

(excerpted from the chapter “The Belasco Project”)

“First of all, I thought the speech was so artificial. Everything seemed affected and sort of pompous to me. Sir John was young and handsome, a beautiful figure on the stage and some of the words affected me, but mostly I thought ‘Why does he have to speak in that fancy way?’ I had already studied Julius Caesar in school and I knew you could say the lines in an American way, even in a Brooklyn way, and still understand them if the passion was there.

Forty-eight years later in 1986, Joe put together a repertory company of actors, mostly young, who were Black, Hispanic, Asian and white to perform Shakspeare for high school students.

“The Black, Hispanic or Asian child begins to understand that his own culture is not something to be concealed or wiped out,” Joe said, “but, on the contrary, it is part of world culture and, as such, is to be nurtured and valued.”

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

(excerpted from the chapter “The Belasco Project”)

Joe also told McKellen about his own teenage experience of seeing Hamlet for the first time. “In 1938, when I was in high school they invited a bunch of us kids to go to Broadway and to see Gielgud in one—and in the other was Leslie Howard. And you know we all had taste of some kind. You always have it on the street. You know a good dancer. You know a good piece of music. You know a good baseball player. So you have taste in this area as well.

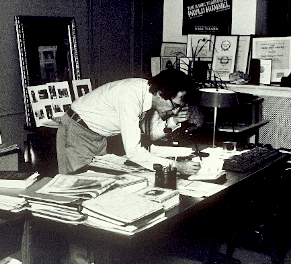

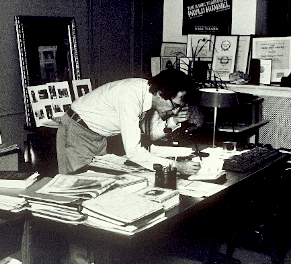

Courtesy of the Papp Estate.

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

Stories

From Gail Merrifield Papp’s forthcoming memoir

On a dark and deserted road

(excerpted from the chapter “Country Matters”)

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

(excerpted from the chapter “The Globe Theater Birdhouse”)

Excerpted from a chapter in Gail Papp’s forthcoming memoir

Photo: Gail Papp